15 Places Where The Trail Of Tears Is Remembered

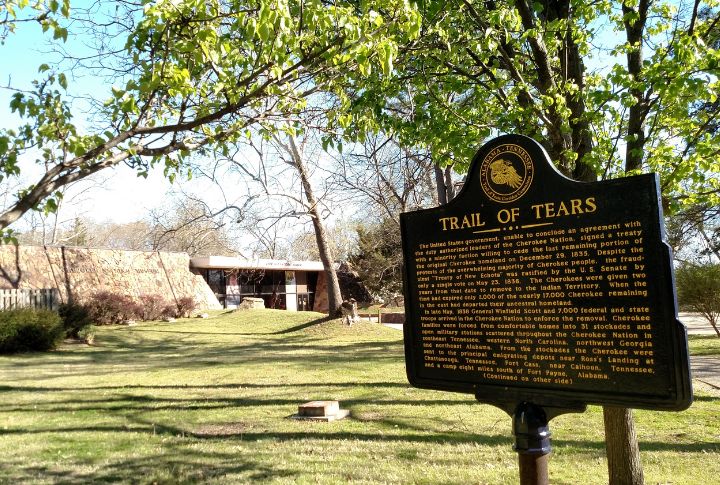

In 1838, over 16,000 Cherokee were forcibly removed from their ancestral lands, which led to the deaths of approximately 4,000 people during the harrowing journey known as the Trail of Tears. Today, a network of historic sites across nine states preserves this tragic chapter in American history. Explore these commemorative sites to gain a deeper understanding of this significant event.

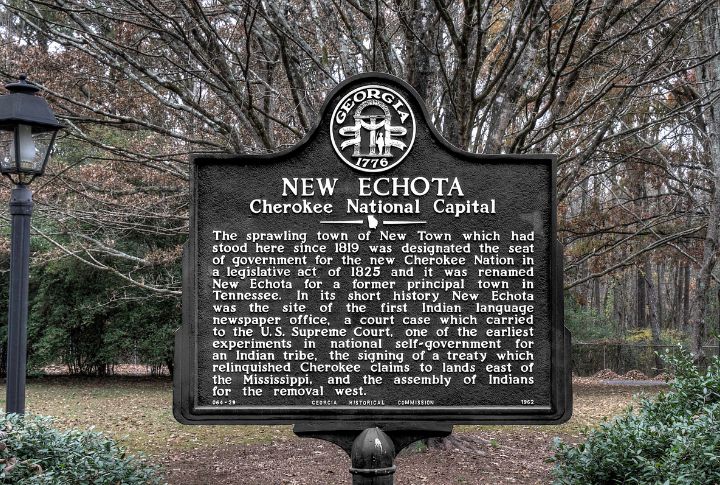

New Echota

In the 1820s, New Echota flourished as the Cherokee Nation’s capital, where written law and a newspaper in syllabary form took root. Few American towns of the era had such a sophisticated structure. Buildings reconstructed today echo what was once a thriving seat of Native governance.

Red Clay State Historic Park

The Blue Hole Spring at Red Clay served as a spiritual anchor for leaders who met there between 1832 and 1838. You can still walk the ground where political resistance stirred under council rooftops. Many final decisions before removal were voiced in this valley.

John Ross House

Few homes carry the emotional weight of this Georgia cabin. John Ross fought for Cherokee rights within these walls before the federal order to vacate their homeland arrived. His legal battles spanned two presidencies. The house stands as a record of quiet defiance under growing pressure.

Fort Cass

Rows of tents surrounded by military guards defined Fort Cass in 1838. Located near Charleston, Tennessee, it held over 4,000 Cherokee awaiting forced migration. Many grew ill during the wait, and as the central internment site, Fort Cass remains one of the most devastating locations.

Blythe Ferry

Over 9,000 people crossed the Tennessee River at Blythe Ferry, stepping into the unknown while leaving everything behind. What once served commerce became the start of exile. Today, interpretive displays honor those final moments on ancestral land, where silence now tells what no monument ever could.

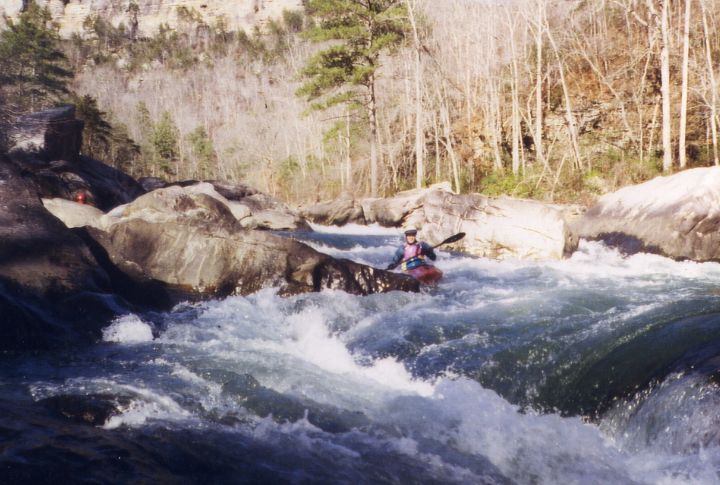

Little River Canyon National Preserve

Alabama’s Little River Canyon remains wild and difficult to traverse. Yet in 1838, many Cherokee detachments crossed it under federal escort. The canyon’s cliffs are now popular with hikers. Interpretive signs carefully track that sorrowful route.

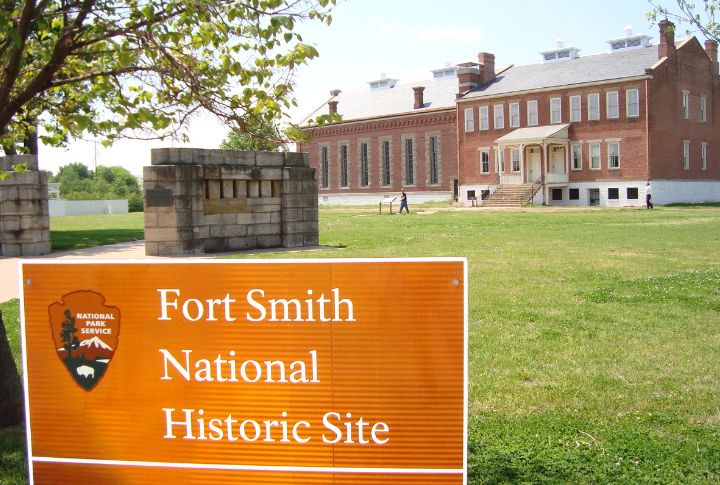

Fort Smith National Historic Site

To some, Fort Smith marked safety after a brutal journey. For others, it brought the shock of new laws and borders. Set in Arkansas, it became the first official stop within Indian Territory. Overlooks and museum displays now capture this shift from captivity to constrained resettlement.

Pea Ridge National Military Park

Hikers at Pea Ridge may not realize their steps mirror those of displaced Cherokee from 1839. The park preserves original trail segments that bore countless footsteps under cold skies. That’s proof that landscape alone doesn’t tell the full story—but paired with history, these dirt paths speak volumes.

Chieftains Museum

Once a peaceful homestead, the Ridge property in Rome later bore heavy consequences. Major Ridge’s decision to sign the Treaty of New Echota led to division—and later, his assassination. The house, now a museum, reveals one man’s controversial legacy and the debate it still sparks.

Tuscumbia Landing Site

Tuscumbia Landing in northern Alabama was a key departure point during the Trail of Tears. Steamboats carried entire Cherokee groups toward Memphis via the river, one of the few water routes used. Though the port is gone, the site remains federally recognized for its role in this forced removal.

Sallisaw Creek Park

Sallisaw Creek Park in Oklahoma sits near the arrival point for several Cherokee detachments, many having walked over 800 miles. This marked their first step into an unfamiliar land. Today, interpretive panels reflect on that moment when the journey ended, but the struggle for identity and survival was just beginning.

Cherokee Heritage Center

Within Oklahoma’s rolling hills, the Cherokee Heritage Center reflects cultural survival after forced migration. Exhibits combine oral tradition and archival material from the 19th century onward. What began as a refuge now holds centuries of resilience.

Lake Guntersville State Park

A quiet stop along the Benge Route now rests beneath the waterlines of Lake Guntersville. In 1838, the detachment led by John Benge used this area to cross the Tennessee River. Maps and plaques around the park can help you trace the journey.

Trail Of Tears National Historic Trail

Thousands of footsteps across nine states—mapped and marked by the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail—document one of the largest forced migrations in U.S. history. With more than 5,000 miles of designated paths, the route connects physical geography to generational grief and cultural perseverance.

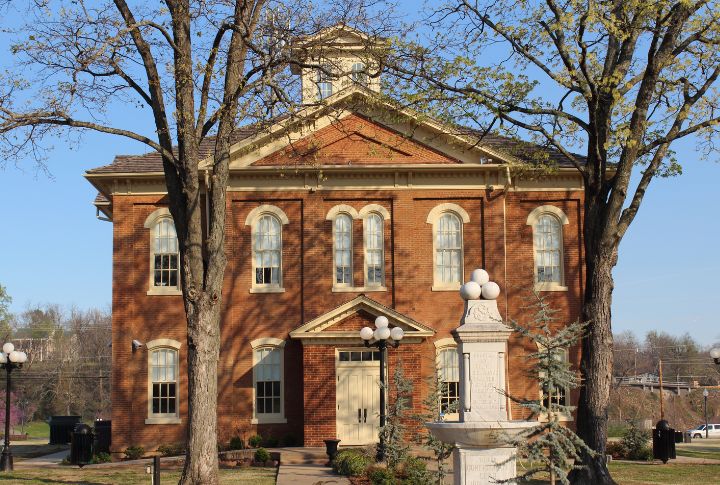

Cherokee National Capitol

After the forced removal, the Cherokee Nation chose Tahlequah—now the capital of the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma—as its new home. Completed in 1869, this red-brick Capitol building became the center of political life. More recently, it has housed the Cherokee judicial system.