Relive Japan’s Warrior Age In These 25 Heritage-Rich Towns

Skip the guidebooks and flashy Tokyo reels. If you want to feel Japan’s pulse, it’s in the villages where samurai once scowled, plotted, and poured tea. Lanterns still flicker while wood floors still creak. So, are you ready to trade Wi-Fi for war stories?

Nagamachi

Nagamachi is proud of its stone alleys that bend between high mud walls, while the Nomura-ke house keeps centuries inside. Samurai ruled this district with more than swords—etiquette here was its battlefield. A missed bow could cost you your reputation

Kakunodate

Kakunodate bursts into pink every spring, but its roots are clad in armor. Samurai once walked these quiet streets; today, visitors enter the same Aoyagi and Ishiguro homes. Built in 1620, they reveal a town shaped more by scrolls than swords—though both left their mark.

Hagi

If you know where to listen, a rebellion buried in pottery and hedgerows still hums. Hagi’s dragon kilns still breathe fire into Hagi-yaki, each piece quietly seething with memory. The Kikuya residence stands mid-defiance. This town helped tilt the Tokugawa shogunate off its pedestal.

Kitsuki

Kitsuki balances two samurai districts on opposing hills, each watching the other with quiet authority. The castle, built in 1394, stands modest yet strategic. Its samurai-era layout—elevated homes and hidden angles—was designed to control movement. Even the architecture observed social rank and military caution in its silence.

Usuki

Stone Buddhas carved in the 12th century keep silent watch, their gaze resting on samurai homes that funded their creation. The warriors here matured into scholars, trading combat for contemplation. Usuki became a seat of learning in the Edo period, known for its Confucian schools and scholarly samurai class.

Matsue

This one’s got a castle that survived and now stands with unshaken presence. Matsue Castle looms while samurai homes keep their heads low. The Buke Yashiki (built in 1730) shows how a low-ranking warrior lived: humble gear and hopefully enough rice rations to last through tax season.

Ainokura

Scenery Samurai? Not exactly. But Ainokura’s villagers built houses tough enough for feudal warm weather. The gassho-zukuri roofs look like hands in prayer but are armor against snow. Isolation was the village’s defense. No sword is needed when the mountain handles your enemies for you.

Suganuma

Suganuma is Ainokura’s even quieter cousin. Think nine houses, zero crowds. You walk in, and time blinks. Edo-era mountain folk lived here under the radar—the perfect hideout if you just offended a daimyo. Thatched roofs still stand watch over what was once a hidden mountain hamlet for farmers and foot soldiers.

Narai-Juku

It’s like walking into a scroll painting. Only this one breathes and smells faintly of cedar and sake. Samurai stayed the night here, slipping into wooden inns along a flawless street. Narai earned its reputation by simply staying the same while centuries shuffled by outside.

Shirakawa-Go

Shirakawa-go went to UNESCO and never looked back. But under the Insta-fame, it’s still a fortress disguised as a postcard. Silkworms thrived in the attic, while valuables hid under thick floorboards as their steep thatched roofs laughed at snowfall.

Iya Valley

Legend says the samurai who lost at Genpei fled here. Iya welcomed them with cliffs and fog. No straight roads, just vine bridges and suspicion. The homes cling to hillsides like fugitives. Even now, the Iya Valley remains remote and rugged—dense forest and vine bridges older than reason.

Tsumago-Juku

This place has rules: no phone poles and no disrespecting the vibes. Tsumago kept its Edo post-town status like a badge. Samurai walked this trail between Edo and Kyoto. Now it’s your turn. Just watch your step, as some of those stones have serious mileage.

Magome-Juku

Magome smells of cypress and something older, like stories sealed into cedar. Its cobbled slopes curve through rows of wooden inns that have welcomed travelers since the 1600s. Not much has changed. Today, you move slower, tracing Edo’s (period of peace) footsteps, noticing details you’d miss on any other street.

Ichijodani

This valley once housed a mini-capital until Oda Nobunaga, Japan’s infamous warlord known for his brutal campaigns to unify the country, burned it to the ground in 1573. What remains are stone paths and deep quiet. You visit Ichijodani to feel lost.

Maruoka

Maruoka Castle, built in 1576, is Japan’s oldest surviving tenshu (main keep). It is known for its original stone walls and calf-testing staircase. A legend claims a human sacrifice lies beneath its base. Modest in size but rich in legacy, the fortress holds tales of feudal resilience and ghostly foundations.

Mikuni

Samurai and sailors clashed in Mikuni’s alleys, then made up during puppet festivals. Yes, puppets. Giant, creepy, fantastic festival puppets still roll through town each year. Today, the harbor is calm, known more for its fresh seafood and access to Tojinbo’s dramatic cliffs than samurai skirmishes.

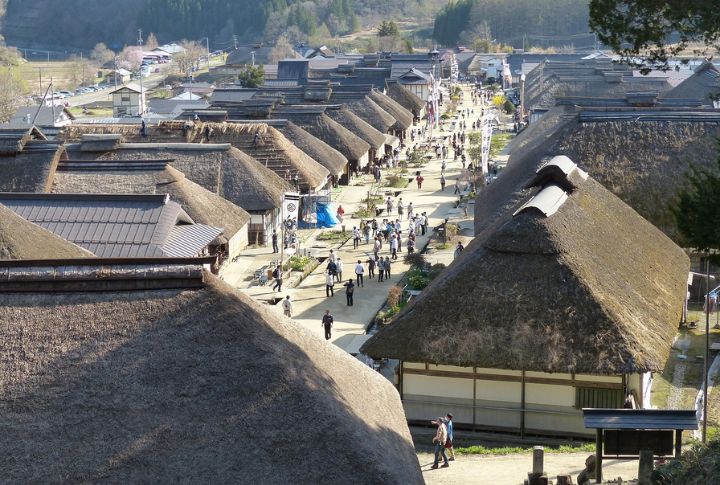

Ouchi-Juku

No wires. No traffic lights. Just thatched roofs and soba shops. This was a refueling stop for feudal couriers; now, it’s where modern stress goes to die. You can find places to slurp handmade soba noodles while sitting on a tatami floor older than your bloodline.

Takayama

Float parades glide through Takayama with all the flair of a silk kimono and the confidence of old money. Sanmachi Street still smells of soy and cedar, which has remained unchanged for centuries. Merchants once held power here, and samurai nodded respectfully.

Gujo Hachiman

Gujo Hachiman comes alive in summer with Gujo Odori, a traditional Bon dance that dates back to the Edo period. For 32 nights, the town moves to a shared rhythm, dancing until dawn. Its clear, drinkable canals and strong community spirit keep its culture flowing year after year.

Tsuwano

Moats full of koi, shrines crawling up hills, samurai homes lining the streets like retired judges—Tsuwano is orderly with an undercurrent of drama. It raised poets and rebels, including Mori Ogai, and once served as a castle town for the Kamei clan during the Edo period.

Omori

Even the silence here feels measured and dignified. Strolling past samurai villas reveals layers of wealth that once funded entire clans. The surface may seem calm, almost suspiciously so. But dig deeper, and you’ll find Omori’s true backbone: the silver-rich Iwami Ginzan mines that quietly bankrolled warlords.

Sasayama

Built by Tokugawa order in 1609, Sasayama was designed as a strategic outpost near Kyoto. Its wide streets and precise grid reflect military intent, while samurai homes still watch from behind paper walls. Today, the castle ruins quietly echo stories of power, loyalty, and control.

Inuyama

A shrine for lost dolls quietly waits among Inuyama’s curiosities, no judgment offered or needed. Down the hill, merchant homes and oddly specific museums—like one entirely about Karakuri puppets—offer their weird charm. Meanwhile, the castle, built in 1537, is viewed from above.

Obuse

Obuse blends tradition with a creative pulse. Old samurai homes now house cafes and sake shops, serving matcha with just enough flair to make Hokusai grin. The ukiyo-e master behind “The Great Wave” painted temple ceilings here in his 80s, showing that art has always led the way.

Shibamata

Forget the Tokyo high-rises. This old-school neighborhood rolls with wooden storefronts and the scent of grilled dango. Shibamata’s claim to fame is Taishakuten Temple, carved in 1929, and film icon Tora-san. In the Edo period, it also served as a residential area for lower-ranking samurai serving nearby estates.