15 Ways Yunnan Keeps The Spirit Of The Ancient Silk Road Alive

Yunnan breathes life into history every single day as ancient trade routes still shape its rhythms. This is not a story frozen in time; it evolves and excels in the present. Ready to see how one region keeps a legendary past alive in the modern world? Explore these remarkable ways Yunnan preserves the enduring spirit of the Silk Road.

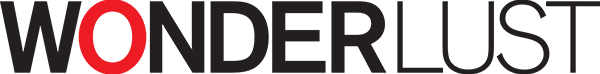

Tea Horse Road Villages Still Trade Puerh Tea By Mule

In parts of Yunnan, Puerh tea still travels the same mountain paths that have been used for centuries. Mules bred locally carry goods where paved roads never reached. Villagers ferment tea in clay cellars, preserving traditional flavor profiles that have been prized by Tibet-bound traders for generations.

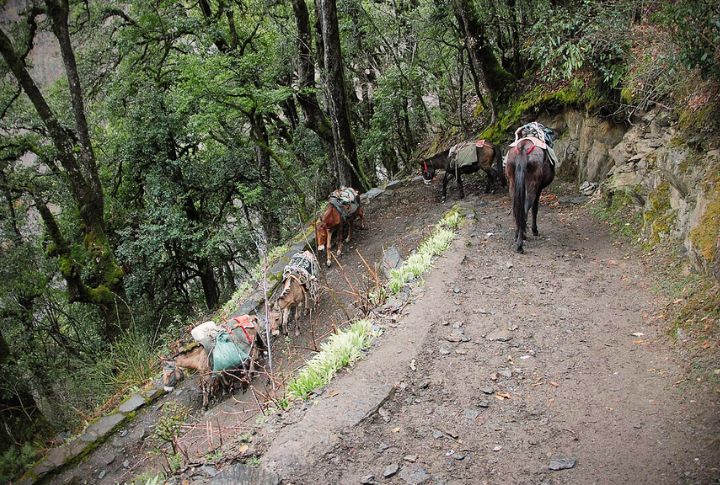

Yunnan’s Naxi Dongba Priests Still Use Pictographs

The Naxi people of Yunnan preserve a pictographic script that is over 1,000 years old. Only a few hundred Dongba priests can still read and teach the Dongba language. Passed down orally, UNESCO now recognizes the endangered script as a rare survivor of pre-alphabetic writing systems.

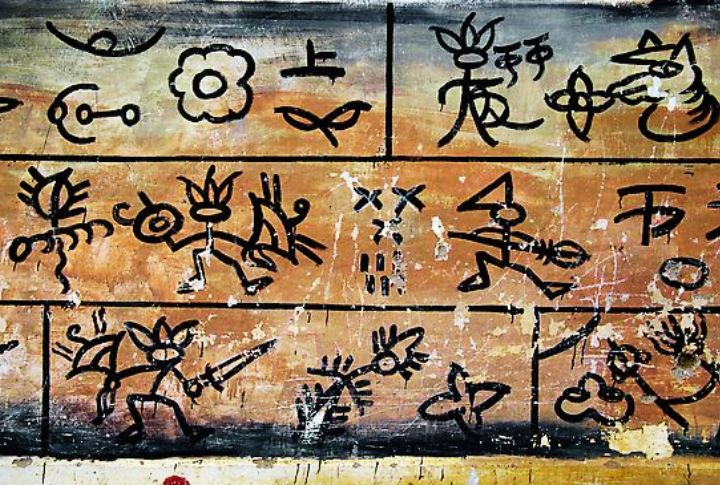

Shaxi Market Operates On A 1,000-Year-Old Caravan Route

Shaxi’s Friday market unfolds in a square once packed with packhorses. Ancient hitching posts still line the space. Traders use dialects that have been spoken for centuries. The town thrived as a hub on the Silk Road, and it remains a vibrant node in regional exchange today.

Jingmai Mountain Tea Forests Are Still Harvested By Hand

On UNESCO-protected Jingmai Mountain, Bulang harvesters climb barefoot into ancient tea trees. The groves have been continuously cultivated for over 1,300 years. Some trees date back to the Tang dynasty, making these leaves a direct link to Silk Road-era agriculture.

Yunnan’s Bai People Still Perform Ancient Salt Rites

In Dali, Bai communities preserve centuries-old salt rituals. Masked dances request trade prosperity, echoing practices from when salt bricks were used as a form of currency. Families still operate salt wells, and intergenerational knowledge keeps the ceremonies active during community and seasonal festivals.

Zhongdian’s Tibetan Horse Festivals Still Draw Nomads

Tibetan horse festivals in Zhongdian showcase breeds that descended from ancient trading stock. Nomadic groups travel great distances to attend these events. Horse races, butter-sculpture contests, and ritual displays mark events once tied directly to regional caravan fairs on the Silk Road’s high-altitude routes.

Nujiang River Rafts Still Ferry Border Goods

Bamboo rafts still carry items like fabric and salt down the Nujiang River, just as they did when trade flowed toward Myanmar. River towns maintain customs houses. Monks bless outgoing vessels, continuing religious and economic rituals along these historic waterways.

Weishan’s Gate Tower Still Oversees Trade Pathways

Weishan’s Ming-era southern gate stands over trade paths used for Silk Road travel. Horse caravans are reenacted annually beneath its arch. The gate still references far-flung destinations, preserving a direct visual and functional link to Yunnan’s role in regional overland commerce.

Ancient Caravan Inns In Lijiang Still Host Travelers

In Lijiang, historic caravan inns with stone courtyards and original woodwork still welcome guests. Built for Silk Road traders, these buildings often contain hidden storage areas once used for goods like salt or copper. They remain functional links to past trade activity.

Mosuo Women Still Trade Via Matrilineal Networks

Among the Mosuo, women lead trade routes that echo the organization of the Silk Road. Salt and barley move through clan lines managed by female elders. The culture’s matrilineal system attracts global researchers interested in how trade customs survive within non-patriarchal family structures.

Zhaotong’s Copper Crafts Continue Silk Road Metalwork

Zhaotong artisans shape copper using tools and fire-blowing techniques passed down since the Han dynasty. Bells and molds reflect the influence of ancient caravans. Handmade with clay and stone, these items preserve functional knowledge once central to East-West trade.

Yi Torch Festival Still Marks Ancient Trade Celebrations

Held every July, the Yi Torch Festival features traditional horse shows, communal meals, and fire dances older than a millennium. Celebrated along caravan roads, it honors alliances and trade routes that once brought various ethnic groups together in shared prosperity and ceremony.

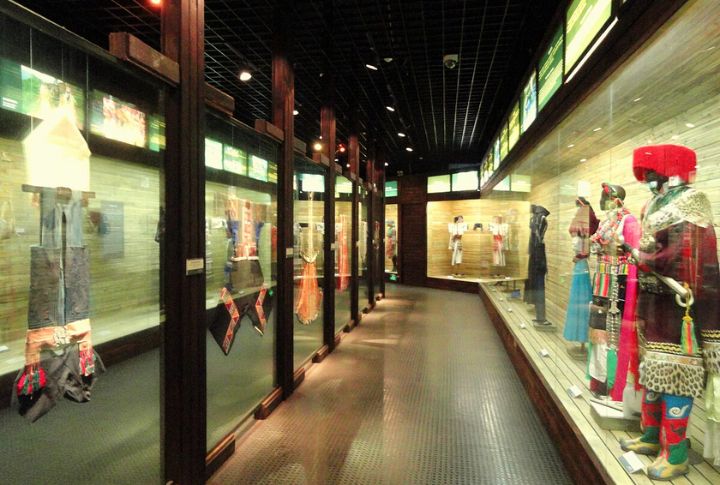

Camel Bells Still Chime In Yunnan Museums

Yunnan’s museums showcase full caravan recreations, including real Silk Road camel bells. Visitors can handle replica goods and listen to chime sounds used for route alerts. Stone-carved maps detail merchant paths, reinforcing how travel and trade shaped the region’s identity.

Stone Roads Near Tengchong Still Bear Hoof Prints

Ancient lava-stone paths near Tengchong show indentations from centuries of pack animal traffic. Some align with Ming-era trade and military posts. Preserved as national heritage corridors, these roads visually preserve the Silk Road’s literal impact on Yunnan’s physical terrain.

Jinuo People Still Trade Tea In Ceremony Garb

Jinuo traders wear traditional clothing and chant ancestral phrases during forest trail exchanges. These routes predate modern roads, and tea is bundled in bark rather than cloth. The practices reflect cultural continuity in how value and identity intersect during trade.